Flying with the 405 pathfinder squadron had its advantages and disadvantages. Often it was the nature of a pathfinder op to be one of the first planes over an intended target. The mission may have involved dropping marker flares on or near an intended target as a guide for other bombers. This may have been an advantage in some ways. The pathfinders may have come and gone before the enemy really realized that a bombing raid was starting and, in that way, Dad figured they may have seen somewhat less anti aircraft fire on some missions. However, because they were marking an intended target and a number of other bombers would be using that mark as a reference, accuracy and a high degree of target confidence was expected by superiors. On some occasions, depending on the conditions, pathfinders dropped some altitude in an effort to get a better visual of a target. Dad once told me, that on occasion, bombs from friendly bombers above could be heard dropping around them as their aircraft left a target area. In at least one case, a bomb actually hit the wing of a pathfinder (not Dad’s plane). It didn’t detonate and the plane was able to fly back to Britain.

Carlyle wrote this concerning his service in the 433 & 405 squadrons:

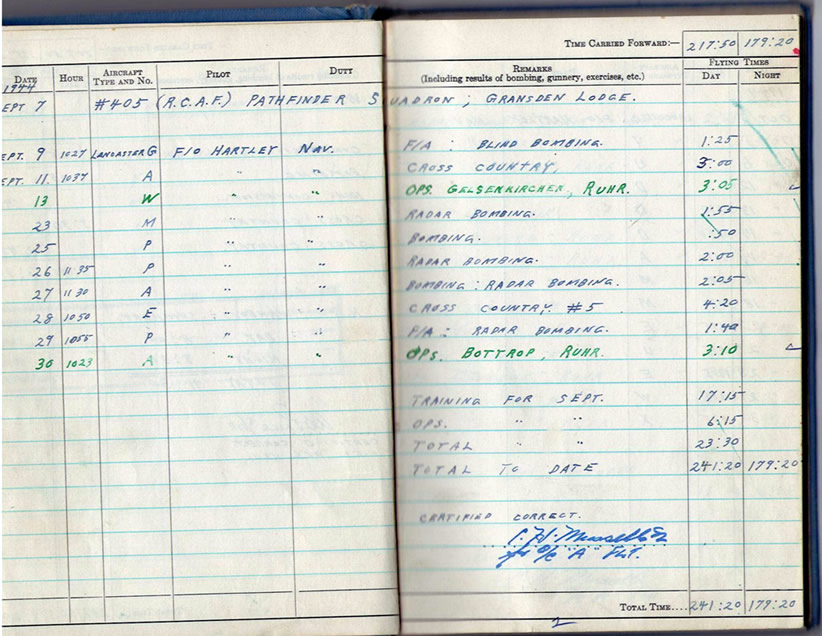

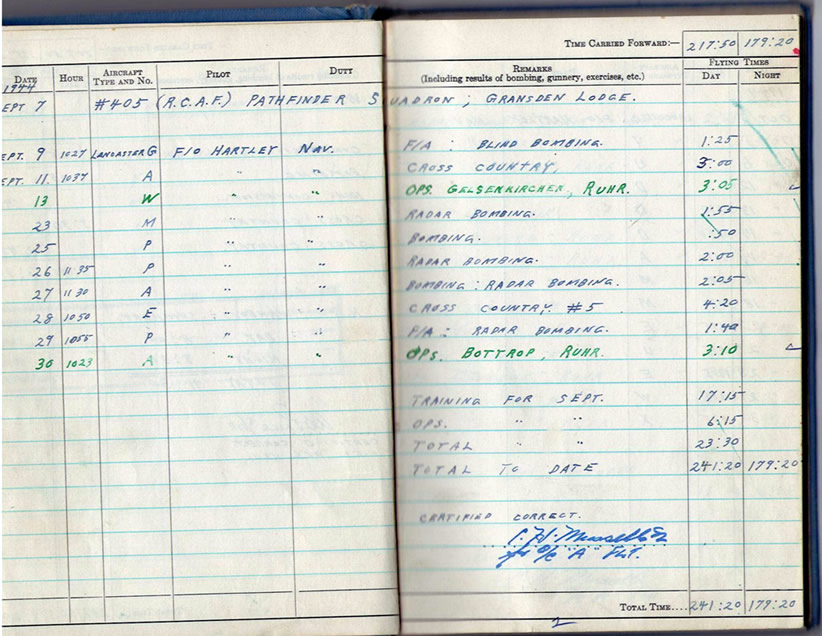

“Normally all crews, after a first tour of duty, were to go on leave to Canada and then return to do a second tour. We went to Pathfinders before we finished a first tour with the provision that we’d automatically do two in succession. We left Skipton on Swale #433 after the twentieth trip and it was our very first one in the 405 where we ran into trouble. We did 36 trips before we finished our first tour. Tours were all based on points. The French buzz- bomb sites were counted for far less than the German Ruhr, hence the quantity. While in the two squadrons, we did 44 trips in total, many of the later ones in the hot belt." (The image below is from the Log Book of John (Jack) Edward Dennis, supplied by his family, and is the first page of the Log Book for flights with 405 Squadron. It shows Op 21 on September 13, 1944.)

|

A few months before he died, Dad shared a few memories of a terrifying flight over Germany. He mentioned that, on two separate occasions, gunners on his flight crew had been injured by flak encountered on bombing missions. Coincidentally, a few months after Dad’s death, Carlyle Chevalier, who had been on the crews of both the 433 & 405 (PFF) squadrons with Dad, tried to contact him. Maureen ended up exchanging several letters with Carlyle and asked if he could provide more details about the flight that Dad had mentioned. He shared a much more complete account of that op and shared many other memories as well.

No. 21, Op Gelsenkirchen, Ruhr, Germany, September 13, 1944

The following comes from a diary kept by Carlyle:

“Daylight mission

Our first trip into the Ruhr, known as “Happy Valley”

Don was our rear gunner and F/S Connolly was our spare mid-upper.

Being our first “P.F.F” trip, we were very bold and stooged over the lower part of the North Sea, the Netherlands and into the Ruhr all alone. Flak was coming up all around while we weaved. Finally three or four burst suddenly right around us with a dull thud. We immediately lost control and also six thousand feet in a few seconds before the pilot pulled it out. Flak followed us all the way down. A fragment went through the perspex in front of the pilot, one bounced off the set-operators oxygen mask, some went through the mid-upper turret slicing the gunner’s collar, scarf and tie. The rear turret was hit and the gunner was hurt quite badly on the head, arm and seat. A piece cut my oxygen tube in two and went into the wireless set in front of me. There was a huge hole in the port wing where petrol was dripping out of a punctured tank. On the return, our parachutes were put on in case it was necessary to bail out. After crossing our coast, we crash-landed at Woodbridge with no air in our port tire. Our kite was full of holes when we landed - the port rudder was useless and the elevator fabric ripped. The night was spent here and we returned to base by truck the next day. No one was lost. The trip lasted three hours.”

In letters written over several years, Carlyle shared more information about that September 13 op. The following, more detailed account, was extracted from those letters.

This was our first trip from 405 Squadron on the Pathfinder Force. Up till then we flew on the 433 Squadron in Halifaxes. On P.F.F., we flew in Lancasters, to my mind a much sleeker bomber - faster and more maneuverable. We were shot at over every target, but none really hit us until this flight. We flew both day and night flights.

We seemed to be over the target alone. I was standing up looking out my astral dome. Flak was all around us and must have exploded right near us because the shrapnel, which sounded like several wires swiping the plane, was, I suppose, going right through us.

As a result of being hit by flak, the following things occurred:

- We nosed down (not intentionally) and dropped six thousand feet in a split second. It was all that the pilot and engineer could do to pull us out of it, but they did. By that time, we were out of the Valley and heading for the area that our troops had captured. We had to fly a route that was full of balloon barrages.

- Our intercom was shot up and we couldn’t hear one another - something that was essential! I had to crawl over the floor of the aircraft with an extension cord to reconnect voice contact between the pilot and Jack so they could communicate to get us home.

- Don Snell, was hit in the head, behind and lost a chunk of the biceps muscle in his arm. Ted Knox-Leet, the set operator, who helped Jack, went back and plugged up the wound. According to Carlyle, Don never flew again.

- The mid-upper gunner F/Sgt Connolly (not our regular gunner) had the lapels of his collar, his tie and his scarf sliced off. The shrapnel was inches from hitting his neck.

- My oxygen mask tube above my head was sliced through and the piece of flak went into the wireless set in front of me. Had I been sitting down at the set, I may have been hit in the head or hands. I remembered looking at the severed oxygen tube and wondering how I was going to breathe at 22 thousand feet - the sudden 6000 foot drop had solved that problem!

- The plane could not gain height, so the flight back to England was quite low

- We flew over France, the English Channel and finally Yorkshire. We landed very near the coast at an emergency drome at Woodbridge. Fortunately, the runway on this airdrome was almost as wide as it was long. Upon landing, we did not slide to the usual stop – the plane went into a circular motion and came to a halt. When we got out, we could see that the plane was absolutely full of holes and it was hard to believe that none of us were more badly injured.

A friend of Dad’s recalled him telling him that the plane once got hit with a lot of flak and some of the navigation equipment was badly damaged. When they had to land due to lack of fuel, Dad thought they were likely above Northern France which was occupied at the time. Luckily they were above Northern England and made a safe landing. We don’t know for certain, but this incident likely occurred on this flight.

Damage to the plane included:

- So many holes that it looked like a sieve. Dad said they counted 200-300 holes - then they quit counting

- A huge hole in the port wing, which resulted in a punctured petrol tank with petrol steaming out. The tanks were self-healing which was fortunate because much more petrol could have been lost.

- One tire punctured flat

- A ripped elevator that was later discovered to be severed - the reason they could hardly pull out of the dive. In a later letter, Carlyle wrote this description – “the aileron connections had been severed, hence we were lucky not only to have pulled out of the dive, but also to have got home.” Carlyle hadn’t learned about the severed elevator connections until Engineer Taffy Williams told him about it in a 1985 visit.

- Dad kept a couple of small pieces of shrapnel. We think he said he dug them out of the plane with a jackknife after they landed.

The next morning the Engineer noted that a bomb had not been released - luckily it hadn’t dropped on the runway and detonated during the landing. When the bomb was discovered, the maintenance crew fled.

The plane landed at sundown. The crew were picked up and taken for something to eat and then to the barracks so they could go to bed.

Dad once commented that his crew didn’t like changes to their crew. We also recall him once saying that he thought his lucky number was 7. His dog tag number was 29329. If you add up all of the digits you get 25 and if you add those digits together, you get 7. Carlyle made the comment that they must have lived a charmed life and had the right people together.

Jim Hartley Crew - Squadrons 433 and 405 - Page 3 continued